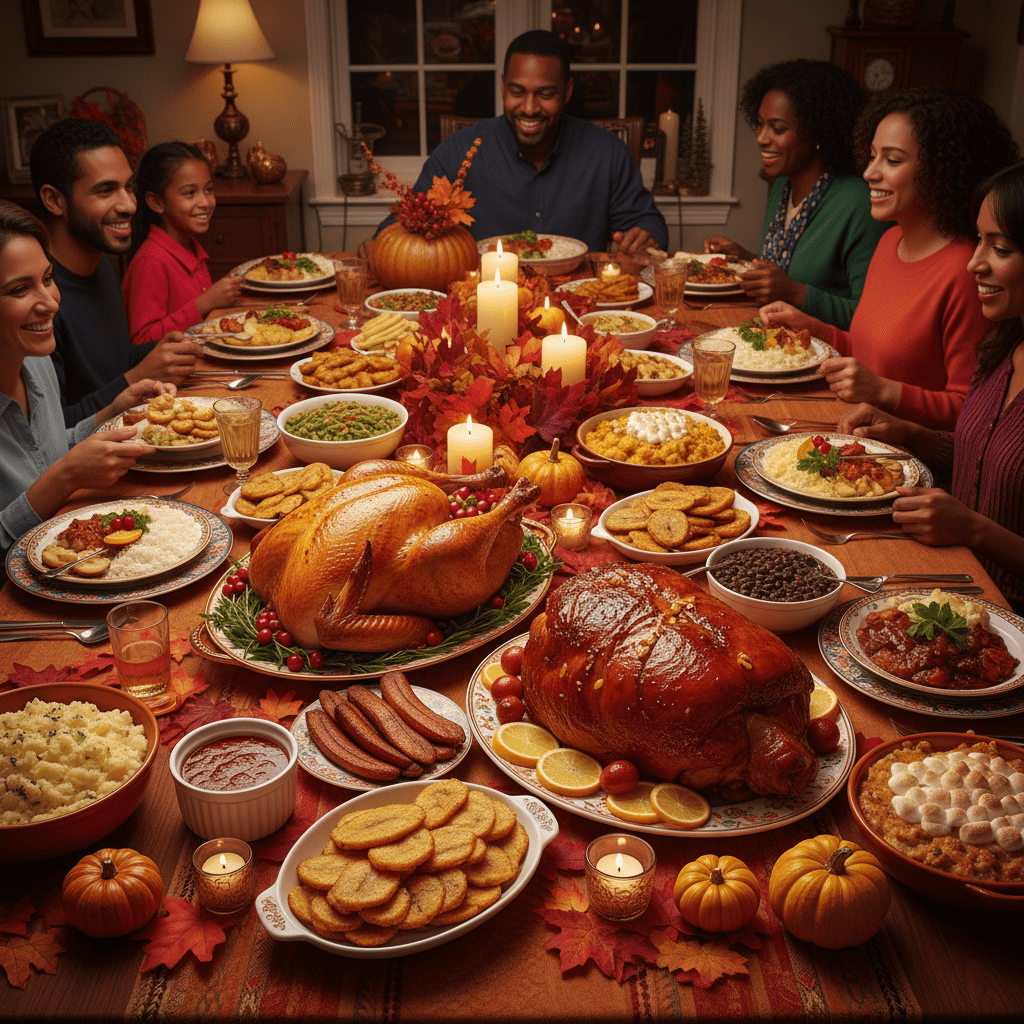

Every Thanksgiving, as the scent of roast pork mingles with the unmistakable aroma of turkey in our Miami apartment, I’m reminded that my family’s story is as complex—and delicious—as the feast itself. Let me take you on a wander through noisy living rooms ringed with abuelos, tables that groan under platters of congri and cranberry sauce, and the little acts of adaptation that make Cuban-American Thanksgiving uniquely ours.

How Cubans Do Thanksgiving: My Family’s Table (And a Few Hilarious Mishaps)

“Thanksgiving was the one American holiday my Cuban family understood.” – Elena Cabral

Growing up in a Cuban-American household, I learned that How Cubans Do Thanksgiving means throwing tradition out the window and creating something beautifully chaotic. Our Thanksgiving table looked nothing like the magazine spreads, but it was infinitely more delicious and definitely more entertaining.

The Great Turkey vs. Lechón Debate

In my family, turkey sometimes played second fiddle to lechón asado. Yes, we’ve had whole pigs roasting in our backyard, caja china style. Picture this: while our American neighbors were basting their turkeys, my uncle was tending to a massive roasting box that looked like it could launch rockets. The smoky aroma of slow-roasted pork would drift across three backyards, making us the unofficial neighborhood flavor champions.

The Cuban Thanksgiving recipes in our house were a masterclass in organized chaos. My father would start the lechón at 5 AM, coffee in one hand, beer in the other, conducting the roasting process like a Cuban symphony. Meanwhile, my mother worked her magic on the turkey, but not without her own Cuban twist – a mojo marinade that would make that bird sing salsa.

Grandma’s Stuffing Rebellion

My grandmother never quite trusted traditional stuffing. “Dry bread? Pues no!” she’d declare, waving her wooden spoon like a weapon. Instead, she’d serve up congri – that perfect marriage of rice and black beans that became our unofficial Cuban Thanksgiving dishes staple. Her logic was flawless: why stuff a bird with bread when you could have perfectly seasoned rice and beans that actually tasted like something?

She’d pile that congri high on our plates, right next to the mashed potatoes, creating what I now realize was a carbohydrate paradise that would make any Cuban grandmother proud.

The Unexpected Menu Crashers

Our Cuban food Thanksgiving spread was like a cultural collision in the best possible way. Between the mashed potatoes and green beans, you’d find unexpected guests: crispy croquetas that disappeared faster than my cousin’s sobriety, golden pastelitos that had no business being on a Thanksgiving table but somehow belonged, and always – always – fresh Cuban bread that we’d fight over.

The dessert table was where Cuban Thanksgiving traditions really shined. Sure, there might be a pumpkin pie somewhere, but it was competing with my aunt’s legendary flan, so silky and sweet it could make grown men weep. I watched American friends try to choose between apple pie and flan. There was no contest – the flan won every single time.

The Deep-Fried Disaster of 2003

The most memorable Thanksgiving mishap happened when my cousin decided to combine American innovation with Cuban flavor. He was going to deep-fry a turkey – but not just any turkey. This bird was going to get the full Cuban treatment: mojo, sazón, cumin, garlic, the works.

Let’s just say that when you inject a turkey with enough Cuban spices to wake the dead and then submerge it in 350-degree oil, things get interesting fast. The garage still smells like cumin fifteen years later, and we’re pretty sure some of those spices are permanently embedded in the concrete floor.

The turkey actually turned out incredible, but we learned that day that Cuban seasoning and deep-frying create an aromatic experience that can be detected from space. Our neighbors still ask about “that smell” every November.

The Beautiful Chaos of Cuban-American Thanksgiving

Heritage on the Plate: Why Thanksgiving History Tastes Different in Cuban-American Homes

When I think about Thanksgiving history in Cuban culture, I don’t picture Pilgrims and Native Americans sharing corn at Plymouth Rock. Instead, I see my abuela’s hands folding napkins around the dining table in Miami, her voice mixing Spanish prayers with English gratitude, creating something entirely new.

The truth is, Thanksgiving history means something completely different when your family arrived on rafts instead of the Mayflower. For Cuban immigrants, this holiday became less about celebrating a mythical first feast and more about honoring the miracle of making it to American shores alive.

“For my parents, Thanksgiving didn’t make sense at first—but now, it’s the holiday when we remember why we’re grateful to be here.” – Ana Maria Perez

Freedom With Every Forkful

Our Thanksgivings focus less on the Pilgrims and more on gratitude for making it to the U.S.—freedom with every forkful. My father used to say that every bite of turkey reminded him of the meals he couldn’t have back in Cuba, the conversations he couldn’t share, the prayers he couldn’t say out loud.

This perspective shapes how Cuban immigrant family traditions approach the holiday. While other families might tell stories about harvest festivals and colonial history, we share immigration stories. We talk about the friends who didn’t make it, the relatives still waiting in Havana, and the incredible fortune of sitting around this table together.

Speaking Gratitude in Two Languages

A brief detour: did you know some families even say grace in Spanish first, then in English? In my house, this bilingual blessing became our signature tradition. My grandmother would begin in the Spanish that carried her childhood prayers, and then my cousins would continue in the English that carried our future dreams.

This language mixing reflects how Cuban-American cultural identity works at the dinner table. We’re not choosing between being Cuban or American—we’re creating something new. The cultural significance of Thanksgiving in our homes becomes a bridge between worlds, a holiday where both identities can exist on the same plate.

Photo Albums and Immigration Stories

Holiday nostalgia hits different when you’re flipping through old photo albums filled with immigration stories. Every Thanksgiving, someone pulls out the pictures—grainy shots of boats, faded passport photos, images of those first apartments in Miami where entire families squeezed into tiny spaces but felt enormous gratitude.

I remember my abuelo explaining why Thanksgiving was strange at first. “We didn’t understand why Americans needed a special day to say thank you,” he’d tell us, chuckling. “In Cuba, after what we lived through, every day felt like Thanksgiving.” But eventually, this holiday became our family anchor, the one day when all the scattered cousins, the ones who moved to Orlando or Tampa, would drive back to Miami for dinner.

When Strange Became Sacred

The evolution of Thanksgiving history in Cuban households mirrors the immigrant experience itself. What felt foreign and confusing gradually became familiar and precious. My parents’ generation learned to love this holiday not because of its American origins, but because of what it allowed them to create—a space for gratitude that honored both their survival and their new home.

These Cuban immigrant family traditions transformed Thanksgiving into something uniquely ours. We kept the turkey but added black beans. We kept the gratitude but added prayers for relatives across the water. We kept the family gathering but made it bilingual, multigenerational, and deeply aware of how precious this freedom really is.

In Cuban-American homes, Thanksgiving doesn’t taste like colonial history. It tastes like survival, hope, and the incredible sweetness of being able to speak your mind at your own dinner table. Every November, we don’t just celebrate a harvest—we celebrate the harvest of dreams that somehow made it across ninety miles of dark water to bloom in American soil.

Improvising Tradition: Thanksgiving Recipes Cuban-Style (and What We Can’t Celebrate Without)

Every Cuban-American family has that one abuela who took one look at the traditional Thanksgiving turkey and said, “Mijo, we can do better than this.” That’s how turkey fricassee became the unofficial compromise dish of Cuban Thanksgiving recipes. Instead of a whole roasted bird sitting lonely on the table, we tear that turkey apart, season it with sofrito, and let it swim in a rich sauce with peppers and onions. It’s like giving the turkey a Cuban passport.

My grandmother never understood why Americans wanted their turkey so dry and plain. She’d shake her head and mutter something about “comida sin sabor” while reaching for her bottle of sazón. The turkey fricassee was her way of meeting America halfway while keeping her kitchen Cuban. It worked so well that now my cousins in Orlando make it every year, and their American neighbors always ask for the recipe.

The Battle of the Starches: Congri Meets Sweet Potato Casserole

If you’ve never seen a Cuban-American Thanksgiving meal, prepare yourself for a carb festival that would make any nutritionist weep. We don’t just serve sweet potato casserole because that’s what Americans do. We serve it alongside our sacred congri dish because, in our world, one starch is never enough.

The congri (rice and black beans cooked together) sits proudly next to the marshmallow-topped sweet potatoes like old friends sharing space at the table. Then there’s the Cuban bread, warm and crusty, because what’s a meal without bread to soak up all those beautiful sauces? My tía always says you need at least three different ways to fill up at dinner, and honestly, she’s not wrong.

These Thanksgiving recipes Cuban style create a table that tells our whole story. The American dishes show where we live now, but the Cuban ones remind us where our hearts started. When my kids complain about too much food, I tell them the same thing my mother told me: “You never know when you might be hungry again, so eat while you can.”

The Great Flan Debate and Other Kitchen Wars

Every year, without fail, the kitchen becomes a battlefield over who gets to make the flan. My aunt Carmen insists her recipe is the only authentic one because she learned it from her mother in Havana. My cousin Maria argues that her version is better because she adds a touch of vanilla that “modernizes” the flavor. Meanwhile, my other aunt quietly makes tres leches cake and acts like she’s not starting trouble.

Then there’s always someone who tries to sneak in a pastelito de guayaba for dessert, as if we need more sugar after the flan wars. But nobody complains when it appears on the table because guava pastries are like little pieces of childhood wrapped in flaky dough.

“The secret ingredient at our table is always abuela’s sazón, no matter what the recipe says.” – Ramon Garcia

Ramon’s words capture something essential about our Thanksgiving recipes Cuban style. We might follow American recipes, but we season them with memories. That sazón isn’t just seasoning salt; it’s the taste of home, the flavor of love, and the bridge between who we were and who we’ve become.

Where Tradition Lives Now

Our Thanksgiving meal Cuban style proves that tradition doesn’t have to stay frozen in time. It can grow, adapt, and make room for new flavors while keeping its heart intact. When my daughter asks why we can’t just have a “normal” Thanksgiving like her friends, I show her our table loaded with turkey fricassee, congri, and three different desserts.

This is normal for us. This abundance, this mix of flavors and stories, this kitchen full of women arguing over recipes while men hover hopefully nearby—this is how we celebrate gratitude. We’re thankful for the country that welcomed us and for the traditions that made us who we are. Our table holds both, and there’s always room for more.

TL;DR: Cuban-American Thanksgivings are a flavorful dance between two homelands—equal parts abuela wisdom and American tradition, always served with extra gratitude.